SOURCE: DAVID WARD sayjaz3@hotmail.com

POSTED: 7 MARCH 2008 - 7:30am HST

The

Federal Reseve has become irrelevant

image above: the Starving Pig piggy bank

by John Hoefle on 7 March 2008 in www.larouchepub.coml Could they really be that stupid? That is the question which comes to mind watching the recent spate of statements by government officials discussing what they see as the problems facing the economy, and what needs to be done to solve them. Rather than admitting the global financial system has failed, and must be put through bankruptcy, they blather on about whether or not we have entered into a recession, and about the need to protect asset values from the effects of what they prefer to call the "housing crisis." Take the case of poor Ben Bernanke, who had the misfortune of taking over as chairman of the Federal Reserve just in time for the worst financial crash in six centuries. Bernanke has a reputation for being an expert on the Crash of 1929 and the banking problems which surrounded it, but judging from his public statements, he still believes we are in the midst of a housing crisis. "Many of the challenges now facing our economy stem from the continuing contraction of the U.S. housing market," Bernanke told the House Committee on Financial Services in his Feb. 27, Semiannual Monetary Report to Congress. We do not dispute that there is a housing crisis in the U.S.; home sales and home prices are indeed falling, precipitously, with predictable effects. What we reject, and emphatically so, is the idea that housing is the cause of the present crisis: As we have detailed in prior articles, it is the bankruptcy of the system as a whole, which blew out the real estate markets. The so-called "subprime crisis" is actually an effect of a financial system which depended upon ever-higher mortgage debts to feed a financial bubble. The subprime loans were a response from the banking system to continue to sell homes when prices rose so high people could no longer afford them. What we are facing is a crisis of the banking system itself, and of the securitization and off-balance-sheet apparatus which the banks created to hide their own bankruptcy, and anyone who is afraid to say that, is irrelevant. Banking Crisis The fact that they refuse to say it, doesn't mean they don't understand it, at least in part. It is clear from the Fed's money-pumping and collateral-soaking operations that the Fed realizes the banking system is in meltdown mode, and it is fair to suspect that the Fed is doing far more than it would dare publicly admit, to keep the banks' doors open. The problem facing the regulators is that the financial system is collapsing, held together more by denial than anything else. The vaporization of trillions of dollars of nominal wealth has triggered an avalanche of losses, losses which the system cannot withstand, and so considerable effort is being expended to maintain the fiction that the bond market hasn't exploded, the paper still has value, and the banks are not broke. The problem is that the event—the collapse of the global financial system—has already occurred, and what we are now witnessing are the effects of that collapse. The FDIC has already begun adding staff to its Division of Resolutions and Receiverships in preparation for a wave of bank failures, and has placed job postings on its website for those with the skills in "duties associated with a financial-institution closing." Three banks failed in 2007, compared to none in the two previous years, and the number of institutions on the FDIC's "problem" list jumped 50%, from 50 in 2006, to 76 in 2007. One need but look at the headlines of the agency's latest Quarterly Banking Profile to see signs of trouble ahead. "Quarterly Net Income Declines to a 16-Year Low," said one; "One in Four Large Institutions Lost Money in the Fourth Quarter" said another. The banks still reported a profit of $5.8 billion for the quarter, the lowest such total since 1991, and down 84% from the $35 billion the banks reported for the fourth quarter of 2006. For the year, the banks claimed $105 billion in profits, down 27% from $145 billion in 2006. In an era where write-offs of double-digit-billions have become almost common, the handwriting is on the wall. The ominous tone of the normally upbeat FDIC report continues well beyond the headlines. Non-current loans—loans 90 days or more behind in payments—rose by $27 billion, or 33% in the last three months of the year, the largest percentage rise in the 24 years the FDIC has been tracking the figure, and net charge-offs jumped sharply. The banks as a whole added a net $15 billion to loan loss reserves, despite which, the level of reserves fell to just 93 cents for every dollar of reported non-current loans, the first time since 1993 that non-current loans have exceeded reserves. In a development of significant interest, the level of derivatives reported by the banks fell during the quarter, to $165 trillion at year-end from $173 trillion on Sept. 30. The level of derivatives for 2007 was still up 25% over 2006, and quarterly drops in derivatives holdings have happened before, but in dollar terms, the $8 trillion drop in the fourth quarter was the largest quarterly drop ever, and in percentage terms, at 5%, it was second only to the $6 trillion (12%) drop in the fourth quarter of 2001, the quarter following 9/11. If the derivatives markets have peaked, then the problems facing the banks are far worse than anything the banks and their regulators have admitted. Other signs of a banking crisis abound. The big banks which own Visa, the world's largest credit-card processor, are planning on selling roughly half of the company in an initial public offering. The IPO is intended to raise some $15-19 billion, giving the banks some badly needed capital, and helping them reduce their exposure to credit cards, one of the many nightmares on the horizon. Raising capital has become serious business for the banks, with Citigroup, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and Wachovia raising over $55 billion in the last few months, to offset some of their losses. While the biggest banks are the most bankrupt, the smaller banks are also in trouble. Figures from the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) show that the commercial real estate exposure of the nation's community and mid-sized banks is in the range of 275% of their capital as of 2006, compared to about 80% for the large banks. Bailouts Numerous bailout proposals are circulating in Washington, all of them based upon the idea that the current asset decline is an aberration, and that the government should step in and protect the asset valuations until the market returns to normal. FDIC chairman Sheila Bair has proposed freezing scheduled interest rate hikes on troubled mortgages. Sen. Chris Dodd (D-Conn.), head of the Senate Banking Committee, proposed that the Federal government purchase and refinance mortgages headed for foreclosure. Bank of America and Crédit Suisse are circulating their own proposals. Many of these proposals involve having the Federal Housing Administration insure loans, and then having Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac buy them; Freddie and Fannie have been instructed to begin buying so-called jumbo loans—those over $417,000—despite the fact that both institutions are already hemorrhaging money. Freddie Mac reported a loss of $2.5 billion for the fourth quarter, while Fannie Mae lost $3.6 billion. All of the plans, while claiming to protect the public, are actually intended to protect the valuations of mortgage-related securities, as a way of protecting the banking system. Rather than admit that housing prices are too high, that debt levels are unsustainable, and must be adjusted through bankruptcy proceedings, the plans would convert the debt to government obligations, in effect shifting the huge asset losses to the taxpayers. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson has attacked some of these proposals as bailouts of speculators, even while advancing his own bailout plans. While some bankers are clamoring to be saved, Paulson is smart enough to realize that the bankers—or at least some of them—will have to take their lumps. He has been adamant that banks must write down their losses and recapitalize, even while he has attempted to organize private-sector bailouts like his ill-fated M-LEC Super-SIV plan, and his Hope Now Alliance. Paulson, as a former Goldman Sachs banker, knows quite well that the financial system is finished, and is determined to save the core institutions of that old system—a handful of big banks, investment banks, and other institutions—to survive as part of the new system the bankers are attempting to put into place. Much of the old system will have to be let go, with the new system to be raised, Phoenix-like, out of its ashes. The politicians are to be kept out of this as much as possible, in Paulson's view, because the new system will rely much more on technocrats than politicians, much more on the private sector than the government. While the technocrats attempt to decide our fate, the news media is doing its best to distract us with minor dramas like the fate of the monoline bond insurers, and all the losses that will follow should the monolines fail to retain their crucial AAA credit ratings. If they fail, we are repeatedly and breathlessly told, all hell will break loose. But, all hell has already broken loose. The monolines wouldn't even be an issue were the bond market not collapsing, a point which ought to be obvious, but which the media continually misses. California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, acting on behalf of fascist bankers like Felix Rohatyn, are touring the country pushing privatization of public infrastructure. They claim the private sector, with all its cash, can afford to build projects the governments cannot, but it is the old bait and switch scam. These private sector funds are rapidly evaporating. The bankers don't intend to spend billions, they intend to make billions by charging ordinary citizens for using infrastructure the citizens have already paid for. It is a very old-fashioned rip-off, and you can expect to pay through the teeth. Assuming, of course, that you survive. |

SOURCE: DAVID WARD sayjaz3@hotmail.com

POSTED: 4 MARCH 2008 - 7:00am HST

The

Federal Reseve Bailout has failed

image above: The front facade of the U.S.

Federal Reserve Bank

| by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, 4 March 2008 on The Telegraph The verdict is in. The Fed's emergency rate cuts in January have failed to halt the downward spiral towards a full-blown debt deflation. Much more drastic action will be needed. Yields on two-year US Treasuries plummeted to 1.63pc on Friday in a flight to safety, foretelling financial winter. The debt markets are freezing ever deeper, a full eight months into the crunch. Contagion is spreading into the safest pockets of the US credit universe. It is hard to imagine a more plain-vanilla outfit than the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which manages bridges, bus terminals, and airports. The authority is a public body, backed by the two states. Yet it had to pay 20pc rates in February after the near closure of the $330bn (£166m) "term-auction" market. It had originally expected to pay 4.3pc, but that was aeons ago in financial time. "I never thought I would see anything like this in my life," said James Steele, an HSBC economist in New York. No sane mortal needs to know what term-auction means, except that it too became a tool of the US credit alchemists. Banks briefly used the market as laboratory for conjuring long-term loans at Alan Greenspan's giveaway short-term rates. It has come unstuck. Next in line is the $45trillion derivatives market for credit default swaps (CDS). Last week, the spreads on high-yield US bonds vaulted to 718 basis points. The iTraxx Crossover index measuring corporate default risk in Europe smashed the 600 barrier. We are now far beyond the August spike. Sub-prime debt is plumbing new depths. A-rated securities issued in early 2007 fell to a record 12.72pc of face value on Friday. The BBB tier fetched 10.42pc. The "toxic" tranches are worthless. Why won't it end? Because US house prices are in free fall. The Case-Shiller index for the 20 biggest cities dropped 9.1pc year-on-year in December. The annualised rate of fall was 18pc in the fourth quarter, and gathering speed. As the graph shows below, US households are only halfway through the tsunami of rate resets - 300 basis points upwards - on teaser loans. The UK hedge fund Peloton Partners misjudged this fresh leg

of the crunch. After an 87pc profit last year betting against

sub-prime, it switched sides to play the rebound. Last week it

had to liquidate a $2bn fund |

SOURCE: JUAN WILSON juanwilson@mac.com

POSTED: 18 FEBRUARY 2008 - 7:30pm HST

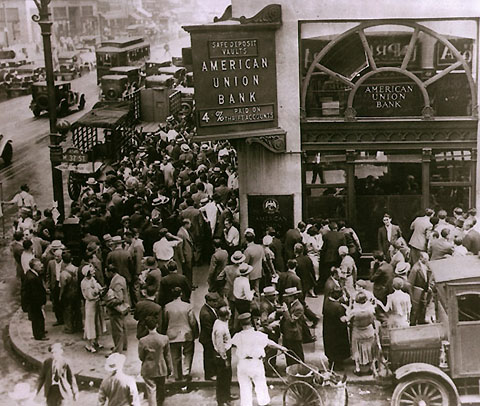

Banks "quietly" borrow

$50 billion from Fed

image above: Bank-run on American Union Bank in 1930's

by Mark McSherry on 18 February 2008 on www.Reuters.com Banks in the United States have been quietly borrowing "massive amounts" from the U.S. Federal Reserve in recent weeks, using a new measure the Fed introduced two months ago to help ease the credit crunch, according to a report on the web site of The Financial Times. |

by James Kunstler on 18 February 2008 on www.kunstler.com The fall of Britain's Northern Rock bank may be the first dropped shoe in a chorus line of big banks tap-dancing into oblivion. The British government's move yesterday to nationalize the insolvent mortgage lender's remaining operations leaves shareholders holding an empty bag. Their only resort now will be to call their lawyers. What we may be witnessing, in a movement that will surely spread to the US, is a changing

of the guard at the top of the financial food-chain between bankers and lawyers. The reason they remain unregulated is the presumption that anybody rich enough to "play" in a hedge fund can afford to lose (or be swindled) with no protection on the sidelines from government busybodies. What's more, the hedge fund managers do not have to make any of their operations open to public view, so that neither the investors nor any regulating authority knows what they are actually doing. And after another while, the nature of money became so detached from anything real, so abstract, that its very existence became hypothetical. Even this "worked" for a while, in terms of the managers of this money being able to "cream" substantial amounts of this hypothetical money off the top of their notional operations and translate that hypothetical cream into Tribeca lofts, Gulfstream jets,

and other real luxuries. And if enough of this bunch showed up at the same time, we would see a phenomenon called a "run" on a bank. And after that started at one bank, the thing Franklin Roosevelt called "fear itself" could easily spread to depositors in other banks pretending to be okay... and that would be the magic moment that the USA discovered it was no longer a rich nation. |