| by Christie Wilson on 4 October 2007 in The Honolulu Advertiser

Two federal agencies raised concerns in 2005 about the Hawaii Superferry's potential impact on humpback whales and other marine mammals and

recommended a "consultation" to examine the interisland service.

The National Marine Fisheries Service and the Marine Mammal Commission were especially worried about the likelihood of collisions between the high-speed ferry and humpback whales, according to officials from both agencies who said they had hoped the U.S. Maritime Administration and Superferry executives would work with federal marine biologists to develop measures to reduce the threat.

The Maritime Administration, known as MARAD, approved a $140 million loan guarantee to Hawaii Superferry on Jan. 21, 2005, for construction of two 350-foot catamarans, later determining that no environmental review of the action was

required.

The Marine Mammal Commission had sent a Jan. 25, 2005, letter to the Pacific Islands Regional Office of the National Marine Fisheries Service expressing surprise that a "Section 7 consultation" under the Endangered Species Act had not been conducted on the potential effects of the ferry service on humpback qhales and monk seals.

The letter from commission Executive Director David Cottingham said the high-speed vessel's "potential for injury of and disturbance to humpback whales and other species is clear," and that any federal agency taking action on behalf of the Superferry "has an obligation to conduct appropriate environmental analyses under federal laws) ... because a 'may affect' situation is obvious."

Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act requires federal agencies to consult with the National Marine Fisheries Service if they are proposing an "action" that may affect listed marine species, which include humpback whales. "Action" is defined broadly to include funding, permitting and other regulatory actions.

The National Marine Fisheries Service sent a letter to MARAD in October 2005 asking whether the maritime agency would be conducting a Section 7 consultation "since we believed there was a threat of ship strikes to protected species," said Chris Yates, head of the service's Office of Protected Resources for the Pacific Islands Region.

According to Yates, MARAD responded in February 2006 that a consultation was not required since the loan guarantee "did not fund, authorize or carry out an action" that would have triggered an environmental review.

Copies of both letters were not immediately available but have been requested by The Advertiser under the Freedom of Information Act.

Yates said in an e-mail to The Advertiser that even if the loan guarantee was a done deal, "had (MARAD) decided to consult, there would have been ample time to analyze the potential effects" of Hawaii Superferry operations on whales and other endangered marine mammals before the start of service.

AGENCY CONCERNED

The company launched service between Honolulu, Maui and Kaua'i on Aug. 26, but suspended voyages the following day due to a Maui court order and anti-ferry protests on Kaua'i.

Tim Ragen, who succeeded Cottingham as head of the Marine Mammal Commission in Bethesda, Md., told The Advertiser last week the agency remains

deeply concerned about "the apparent lack of environmental analysis" of the Hawaii Superferry.

He disagrees with MARAD's decision to exclude the loan guarantee from the review under the National Environmental Protection Act.

The Marine Mammal Commission is an independent government agency created to provide oversight of the marine mammal conservation policies and programs being carried out by ederal regulatory agencies.

"(MARAD) took an action in order to make the loan guarantee. If Hawaii Superferry was able to operate based on that action, then the act itself had consequences that would have been sufficient to initiate a Section 7 consultation," said

Ragen, a marine mammal biologist who studied monk seals in Hawai'i during the 1990s.

"That was how we interpreted it and we were surprised there was no consultation."

MARAD officials in Washington, D.C., have not responded to an Advertiser request for comment.

But MARAD official Jean McKeever testified Sept. 14 in an ongoing Maui Circuit Court hearing that an environmental review of the loan guarantee was not required because her agency was not providing a direct loan or funding to Hawaii Superferry.

The Hawaii Superferry's potential for whale strikes has been a main topic of testimony in the court hearing, now in its fourth week, to determine whether the company should resume service while the state Department of Transportation conducts an environmental assessment of $40 million in ferry-related projects at Kahului, Nawiliwili, Kawaihae and Honolulu harbors.

WHALE-AVOIDANCE PLAN

Hawaii Superferry officials say they consulted with experts to devise an unprecedented whale-avoidance policy that goes well beyond anything in practice by other interisland cargo or passenger carriers. The policy includes avoiding waters of 100 fathoms (600 feet) or shallower where humpback whales are known to congregate during the winter. When that is not possible due to poor sea conditions, the vessel will slow to 25 knots or less while traversing shallower

waters.

The normal ferry cruising speed is 37 knots, or about 43 mph, making it the fastest commercial vessel in Hawaiian waters.

The policy provides an alternate winter route from Honolulu to Kahului that travels north of Moloka'i, instead of the usual route between Moloka'i and Maui within the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary. The company also will post two dedicated lookouts on board to assist the bridge crew in spotting whales.

RISK DISPUTED

Jeffrey Walters, the state's co-manager of the whale sanctuary, has said staying out of waters of less than 100 fathoms when possible during whale season is the most important element of the company's whale-avoidance policy. He said that if

the company adheres to its policy, the ferry presents no greater risk to humpbacks than other vessels operating in whale waters during whale season.

Terry O'Halloran, Hawaii Superferry director of business development, said the company has a "great" whale-avoidance policy that goes as far as it can to reduce the collision risk, pending availability of technology such as forward-looking sonar.

O'Halloran was chairman of the advisory council to the national marine sanctuary, but not yet a Hawaii Superferry employee, when the panel voted to support its whale-avoidance policy in May 2005. The council comprises volunteers representing business, tourism, ocean recreation, Native Hawaiian, government, conservation and community interests.

Sanctuary Manager Naomi McIntosh of the National Marine Fisheries Service said that at the time the advisory council voted to support the policy, the panel recognized the need to publicize the company's plans and considered it "a working document to be revised if safer measures were identified." And since it appeared that no environmental review would be legally required, the policy "represented the best that can currently be done to avoid

such collisions," she

said in an e-mail to The Advertiser.

"While Hawaii Superferry's whale-avoidance policy is a good starting point, the sanctuary believes that it does not go far enough to protect endangered humpback whales in Hawai'i's waters and needs to be strengthened," McIntosh said.

SPEED RAISES FEARS

While praising the company's efforts to address concerns about whale strikes, McIntosh, Yates, Ragen and others remain concerned the big ship will be traveling too fast for its crew to spot whales and avoid collisions, and that the vessel's speed increases the risk of serious injury and death to whales.

Ragen said that "even 25 knots is remarkably fast."

"High-speed ship strikes are a significant issue with North Atlantic right whales and humpback whales, and ship size and speed are a factor. The higher the speed, the more difficult it is to avoid animals, especially in this case when you

have a dense congregation of lots of whales," he said.

"This is the kind of issue where everyone would benefit from consultation, which could have identified measures to reduce the risk to whales.

The essence of consultation is that you can consult with agencies responsible for

protection," according to Ragen. "Anyone can always find a set of experts, but you need objective experts who can look at this from all different perspectives."

EXEMPTION ISSUED

After approving the loan guarantee in January 2005, the Maritime Administration issued a "record of categorical exclusion determination" on March 15, 2005, indicating the loan guarantee did not require further review under the National

Environmental Protection Act because it would not result "in a change in the effect on the environment."

Yates said that as far as he knows, MARAD did not make an informal check with his agency on any potential effects before granting the exclusion.

The determination record also notes that when MARAD reviewed the proposed loan guarantee in December 2004, "there appeared to have been very little, if any, (federal) or state environmental work performed related to the proposed ferry

service." However, on Feb. 23, 2005, the Hawai'i Department of Transportation issued its own environmental exemption to the "minor" improvements at four harbors to accommodate the Hawaii Superferry.

MARAD cited the state exemption as its other reason for granting the federal exclusion.

The Hawai'i Supreme Court ruled in August the state exemption was a mistake because the Hawai'i DOT considered only the harbor projects alone, without examining the potential impacts of their intended user, Hawaii Superferry.

Yates said that since 2005, the National Marine Fisheries Service "has proactively engaged various parties, including Superferry officials, to express our concern over possible impacts to (Endangered Species Act) listed marine species.

Those discussions outlined our concern over the threat of ship strikes to protected species, particularly humpback whales."

"Our contact included meetings and several letters. We outlined our concerns about the continued potential for ship strikes despite the commendable efforts Superferry had already made on its whale-avoidance policy."

NO AUTHORITY TO ACT

Yates also pointed out that despite its concerns, the agency does not have authority to impose itself into the Superferry issue. One federal agency cannot require a consultation with another federal or state agency or a private business

that is undertaking an action that may effect the environment, he said.

However, the action may be subject to litigation, and the Sierra Club, Maui Tomorrow, the Kahului Harbor Coalition and Friends of Haleakala National Park challenged the MARAD exclusion in federal court in August 2005. U.S. District Judge Helen Gillmor dismissed the suit in September 2005, ruling that decisions regarding federal loan guarantees by law cannot be contested. She did not rule on whether the exclusion was proper.

Since the National Marine Fisheries Service could not force MARAD into a consultation, the agency approached the Hawaii Superferry about voluntarily applying for a "Section 10" incidental-take permit, which would protect the

company from prosecution for illegally injuring or killing marine mammals in the event of a collision.

As a condition of obtaining a permit, applicants must work with the service to develop a conservation plan specifying actions that would minimize the risk of harm and show there would be no appreciable impact on the survival of the

species in question.

Yates said a Section 10 consultation with Hawaii Superferry could have been completed by the time the ferry started service, but the company declined to apply for a permit.

When asked about whether the company was considering applying for an incidental-take permit, O'Halloran said the ferry "is leaving all avenues open."

No other vessel operators in Hawai'i have sought incidental-take permits, Yates said.

click at right to comment Island Breath Blog

see also:

Island Breath: Council HSF Resolution 10/4/07

Island Breath: Recent Superferry News 9/29/07

Island Breath: Superferry Lawsuit Links 9/17/07

|

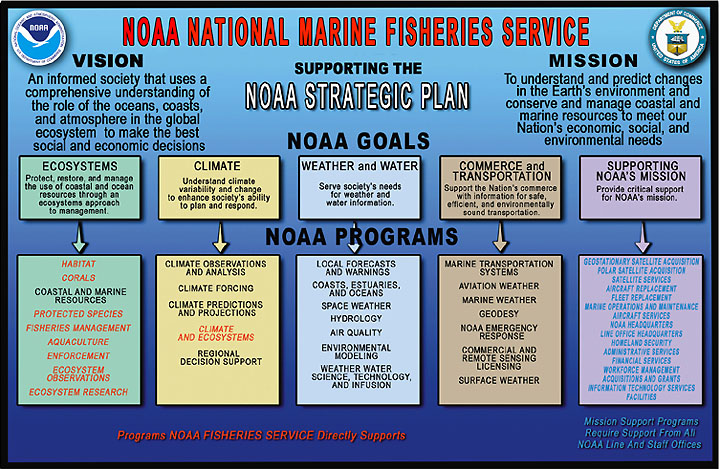

image above: overall organizational view of the National Maritime Fishereies Service

image above: overall organizational view of the National Maritime Fishereies Service